Who wrote Lamentations? Classical opinions, going back to the Talmud, claim that it was Jeremiah, the prophet who warned Jerusalem that this calamity would happen and then had to live through the bitter end - and write about it. More modern scholars question this claim but there’s little doubt that the author/s lived in close historical proximity to horrors and collected first hand evidence of the suffering. As we know too tragically from our own times - the stories of survivors are critical to not only preserve the pain but to take responsibility for what has happened, and to also make sure we learn from history and try to prevent traumatic wars from occurring again and again. Or so we hope.

What’s shocking about Lamentations is the multi-vocal approach used by the authors to convey the dimensions, both personal and public, of the pain. The first chapter focused on the nation of Zion and the city of Jerusalem depicted as the wife turned widow, desecrated daughter and mourning mother.

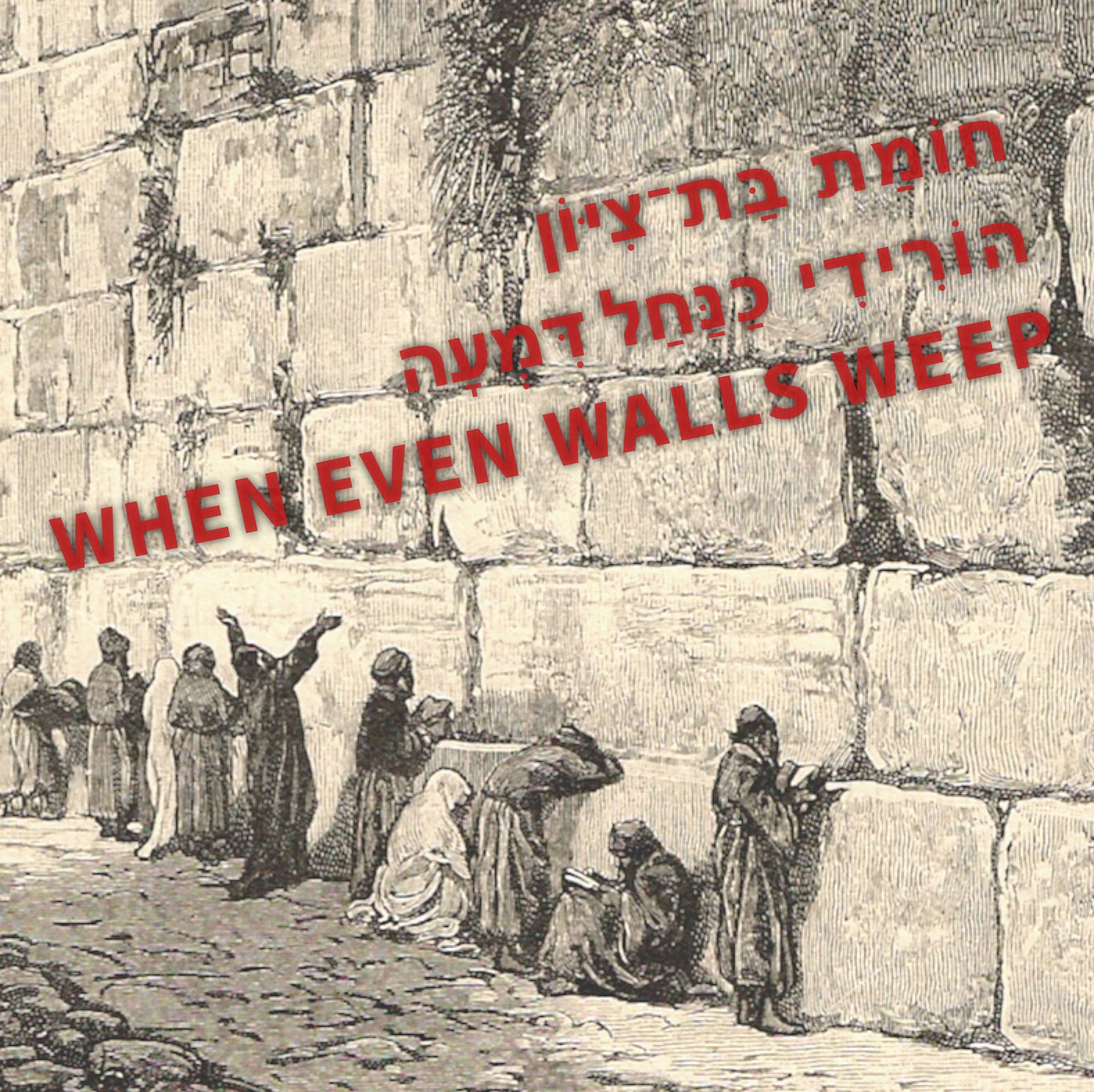

In the second chapter it is the stones of the city themselves that weep, along with the walls of the humiliated capitol. The chapter, also in alphabetical acrostic order, names the horror and also the blame - it was all God’s doing, punishing Judah for disobedience and injustice - over many generations:

חָשַׁב יְהֹוָה לְהַשְׁחִית חוֹמַת בַּת־צִיּוֹן נָטָה קָו לֹא־הֵשִׁיב יָדוֹ מִבַּלֵּעַ וַיַּאֲבֶל־חֵל וְחוֹמָה יַחְדָּו אֻמְלָלוּ׃

GOD resolved to destroy the wall of Fair Zion—

Measuring it with a line, refraining not from bringing destruction.

Wall and rampart have been made to mourn, together they languish.

Lamentations 2:8

צָעַק לִבָּם אֶל־אֲדֹנָי חוֹמַת בַּת־צִיּוֹן הוֹרִידִי כַנַּחַל דִּמְעָה יוֹמָם וָלַיְלָה אַל־תִּתְּנִי פוּגַת לָךְ אַל־תִּדֹּם בַּת־עֵינֵךְ׃

Their heart cried out to the Sovereign. O wall of Fair Zion, Shed tears like a torrent. Day and night! Give yourself no respite, your eyes no rest.

Lamentations 2:18

What’s incredible about some of these poetic details is that the authors seem to have borrowed them from previous poetry - written by the Babylonians themselves, to describe their own original destructions and national traumas.

Prof. Edward L. Greenstein provides astounding prior poetry from the ancient Near East:

“At the end of the third millennium B.C.E., the dominant regime of southern Mesopotamia, the third dynasty of Ur, crumbled under the pressure of foreign aggressors and under the weight of its internal problems. During the following century (the 20th B.C.E.), Babylonian lamentation priests composed at least five lengthy laments in which they interpreted the catastrophes as the venting of the high gods’ anger, but also cited the foreign elements that perpetrated the disasters. The purpose of the laments is to assuage the gods’ anger, to enable the rebuilding of the temples, and to restore the gods to them. In the Lamentation over the Destruction of Ur, not only are the cities and their gods in grief, but the brickwork of the cities grieves as well:

O city, the wailing is bitter, the wailing raised by you!...

O brickwork of Ur, the wailing is bitter, the wailing raised by you!..

O shrine, Nippur, O city (of Nippur), the wailing is bitter, the wailing raised by you!

O brickwork of (the) Ekur (temple), the wailing is bitter, the wailing raised by you!...

O brickwork of (the city of ) Isin, the wailing is bitter, the wailing raised by you!...

O brickwork of Uruk land, the wailing is bitter, the wailing raised by you!

O brickwork of (the city of Eridu), the wailing is bitter, the wailing raised by you!...

O city, though your walls rise high, your land has perished from you!”

Greenstein, quoting other scholars, claims that it is implausible to link direct influence from these historical litanies on the composition of the lamentations. But it’s powerful to imagine that on some level, the Judean refugees who wept the tears of their destroyed city used the same poetic trope that was written by the ancestors of the Babylonians who burned Jerusalem.

What Greenstein also points out is that while the tears of the walls and bricks of Jerusalem are described in detail - an important feature of the collective grief is noticeably missing: Why does God not grieve? Where are God’s tears?

As many scholars have pointed out over the years, the theology that is at the heart of this poem is familiar from the prophetic text and other biblical contexts. YHWH’s rage at Israel for not following the laws and preferring idols, greed and nationalistic zeal over loyalty, human care and compassion is the reason for the horror. Throughout this chapter the divine wrath is described as punishment. Why would God cry when it’s the rage that is the defining emotion?

But for later generations, the absence of God’s tears is unbearable.

Greenstein writes that

“For the sages, as for many other texts in the Bible, the Divine is both just and punitive—and sensitive and merciful. God maneuvers between the principle of compassion (middat ha-raḥamim) and the principle of justice (middat ha-din). Accordingly, whereas the God of Eikha sheds no tears over the destruction He has wrought, the God of Midrash Eikha Rabba not only cries—he shows himself to be a virtuoso of grieving.”

Midrash Eicha Rabba, likely composed during the 1st Century CE, under Roman rule, is the sages’ attempt to read Lamentations with some sort of consolation that predates their own fate - the destruction of the second temple that likely occurred shortly after. In one of these poetic depcitions, the sages fill in the blanks that they see in the scroll by depicting God’s grief and describing the divine tears:

“The Blessed Holy One said to the angels: “Let us go, I and you, so that we may see what the enemies have done to my temple.”

Straightaway went off the Blessed Holy One and the angels, with the prophet Jeremiah in the lead. When the Blessed Holy One saw the Holy Temple, God said: “This is indeed my House, and this is my Resting Place, into which enemies have entered and done as they pleased.”

At that moment the Blessed Holy One began crying and said: “Woe is me over my House! My children—where are you? My priests—where are you? My intimates—where are you? What can I do for you? I gave you a warning, but you did not repent of your ways!”

Centuries after anonymous sages imagined this grief, the images of desolation and consolation continue to haunt the memories of Jewish people, and the longing for redemption fueled the faithful quest for restoration, through the ages. The one remaining wall of the second Jerusalem Temple became the holder of many of these hurts and hopes - the Western Wall known also as the Wailing Wall.

The tears shed at this sacred site for generations continue the tradition that began with the words of lamentations. When even the walls weep along with humans, can human hearts that are not made of stone, soften, grow kinder, learn how to forgive, seek peace, get over the traumas of the past - and heal? If walls could talk.. what would they teach us today?

Below the Bible Belt: 929 chapters, 42 months, daily reflections.

Become a free or paid subscriber and join Rabbi Amichai’s 3+ years interactive online quest to question, queer + re-read between the lines of the entire Hebrew Bible. Enjoy daily posts, weekly videos and monthly learning sessions. 2022-2025.

Become a Paid Subscriber? Thank you for your support!

#Eycha #Lamentations #fivescrolls #hebrewbible #כתובים #Ketuvim #Bible #Tanach #929 #איכה# חמשמגילות #labshul #belowthebiblebelt929 #Eycha2

#wailingwall #westernwall #kotel #doesgodweep? #babylon #poetryofgrief #trauma #exile #DestructionofJerusalem #Jewishtrauma #howdoweheal? #Nippur#whowrotethebible? #howtogrieve #tearsnowords #acroystic #jewishsurvival

#peace #prayforpeace #nomorewar

Rocks they share with us geologic time, the time of all ages, the time from the beginning to the time of now to the eternal so for them to hold all that has transpired since Creation comes as no surprise. So perhaps it is not “even” walls weep but simply “when” walls weep we see the fullness of our individual grief, our groups grief and the grief of all others as connected and as such being able to find forgiveness and peace with one another.

This is powerful. The idea about the bablonian literature over their losses is interesting, even if it isn't clearly accurate, but the idea that the nation who destroyed our holy places and exiled us, have experience of destruction and exile themselves is worth noting. That having suffered exile isn't enough to make you not cause another exile.

May our hearts soften and lead us to restoration and sustainable peace.