Why Exhale Empty Words?

Job 27:11-12

Chapter 27 is the start of Job’s final response to his peers and the tone feels familiar from closing remarks at big trials. And indeed, Job begins his words here with an oath - he is summoning God to a trial and swears that his truth and commitment to integrity will continue to guide his way. Despite his friends’ conviction that he must have sinned to get punished, Job continues to insist that he is guiltless - and that therefore the system itself is wrong.

In The Book of Job: When Bad Things Happened to a Good Person, Rabbi Harold Kushner points to this chapter as one of the pivotal moments of the book:

“I love this passage, for its language as much as for its theology. No matter how often I read it, I am thrilled by the clarity and passion of Job’s words. One senses that the book is moving toward its climax.

This is Job at his best, challenging the God he continues to believe in to live up to His own professed standards of truth and justice.”

Job’s words are directed at his peers and his new direction is not just rage or disappointment but a new demand for justice without compromising his truth.

In the middle of the chapter he makes a bold claim that has something to do with the notion of truth itself: How do we know what we know that gives our opinions such conviction? Can we learn to see core values and beliefs through another lens?

אוֹרֶה אֶתְכֶם בְּיַד־אֵל אֲשֶׁר עִם־שַׁדַּי לֹא אֲכַחֵד׃ הֵן־אַתֶּם כֻּלְּכֶם חֲזִיתֶם וְלָמָּה־זֶּה הֶבֶל תֶּהְבָּלוּ׃

I will teach you concerning the hand of God: that which is with the Almighty will I not conceal.

Behold, all you yourselves have seen it; why then do you thus altogether breathe emptiness?

Job 27:11-12

Job accuses the friends of ‘breathing emptiness’, otherwise translated as ‘why talk nonsense’?

Hidden in these words however is a reference to the oldest human crime and the question that is at the heart of this chapter - how do we know what we know?

The Hebrew word translated here as “nonsense” or “emptiness” is hevel, a term as rich with meaning as it is ambiguous. Elsewhere in the Bible, hevel appears in Ecclesiastes as “vanity” or “futility,” describing the transient, fragile nature of life. Hevel is our outbreath, it’s fleeing air and not solid matter.

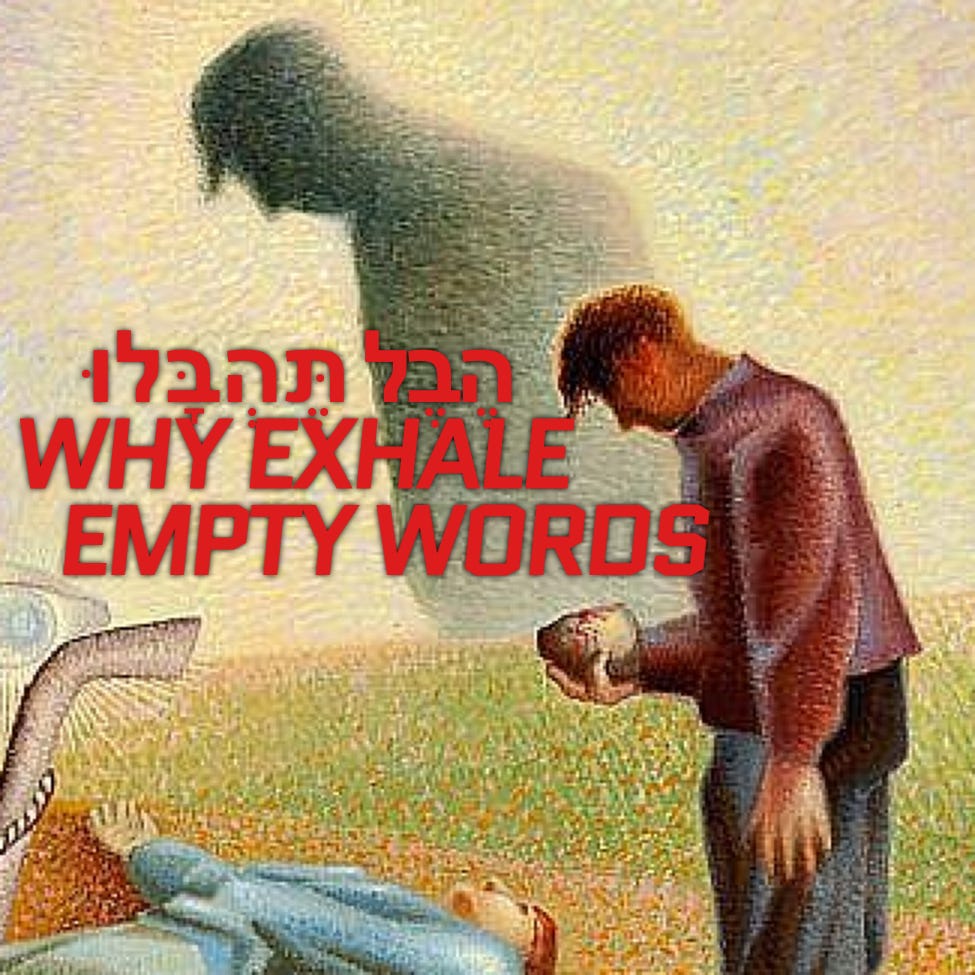

But hevel is also Abel, the tragic son of Adam and Eve, whose senseless murder by his brother Cain underscores the chaos and injustice of the human condition, right from the beginning. Abel is the fleeing vapor while Cain is the solid matter. So what is Job also talking about here?

At its core, Job’s lament in this chapter is a question of knowledge: how do we reconcile what we see with what we believe? Between big ideas ephemeral as vapor and concrete solid factsJob confronts his friends for their theological certainty—their rigid rationalism that claims to understand God’s ways perfectly. Bildad, Eliphaz, and Zophar insist that Job’s suffering must be a result of divine justice, even when the evidence of Job’s blameless life contradicts their assumptions. Job’s retort—“Why talk nonsense?”—is a piercing critique of their refusal to face the messy, empirical reality of his suffering. Was Abel guilty? Was Job?

This debate touches on an ancient philosophical divide. On one side are rationalists, who argue that our minds supply immutable frameworks for understanding the world. On the other side are empiricists, who insist that knowledge must be derived from experience, even when that experience shatters our prior beliefs. Job’s friends are theological rationalists, clinging to their preconceived notions of divine justice. Job, however, embodies a kind of spiritual empiricism. He cannot deny the new, painful evidence of his own life, and this forces him to reconsider the nature of God and the meaning of justice.

The word hevel deepens this tension. Abel’s story is a stark illustration of hevel—the futility and fragility of life when confronted with violence and injustice. Rabbinic tradition often notes the irony of Abel’s name, which signifies transience, as he becomes the first victim of senseless human conflict.

Job’s hevel, like Abel’s, challenges us to resist easy answers. It invites us to hold space for paradox and to seek understanding in the void, where faith, doubt, and experience collide. The question remains: can we find meaning in the hevel—the no-sense, the breath, the fleetingness of life—without succumbing to despair? Job leaves the question unanswered, but he insists we must keep asking. With very exhale we confirm our existence, and with every breath we keep word we speak we continue to echo Job’s demands for a world driven by more justice and less guided by senseless wrongs.

Image: Erik Olson: Cain and Abel, 1942

Below the Bible Belt: 929 chapters, 42 months, daily reflections.

Become a free or paid subscriber and join Rabbi Amichai’s 3+ years interactive online quest to question, queer + re-read between the lines of the entire Hebrew Bible. Enjoy daily posts, weekly videos and monthly learning sessions. 2022-2025.

Become a Paid Subscriber? Thank you for your support!

#Job #IYOV #Job27 #hebrewbible #כתובים #Ketuvim #Hebrewbible #Tanach #929 #איוב #חכמה #labshul #belowthebiblebelt929

#CainandAbel #vanitas #emptywords #hevel #rationalists #empiricists ##rationalistsvs#empiricists

#peace #prayforpeace #nomorewar #hope #peaceisposible #life’sbigquestions #shalom